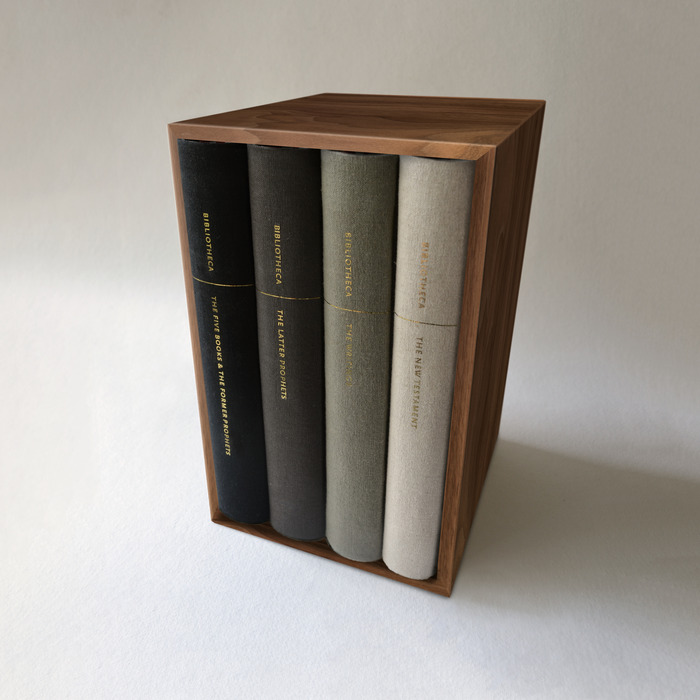

Interview with Bibliotheca's Adam Lewis Greene: Part 2

This is the second part of my interview with Bibliotheca's Adam Lewis Greene. If you haven't read Part 1, start here. Last time we talked about the origins of the project, Adam's passion for the Bible and good design, and the thought that went into designed Bibliotheca's original typefaces. In this part, I ask Adam about the layout, his choice of the American Standard Version, and what the runaway success of the funding campaign might mean for Bibliotheca's future.

This is the second part of my interview with Bibliotheca's Adam Lewis Greene. If you haven't read Part 1, start here. Last time we talked about the origins of the project, Adam's passion for the Bible and good design, and the thought that went into designed Bibliotheca's original typefaces. In this part, I ask Adam about the layout, his choice of the American Standard Version, and what the runaway success of the funding campaign might mean for Bibliotheca's future.

J. MARK BERTRAND: Your decision not to justify the text column threw me at first. Now I think I understand, but since I’m a stickler for Bibles looking like books meant to be read, and novels are universally justified, could you explain what’s at stake in the choice to leave the right margin ragged?

ADAM LEWIS GREENE: This goes back, again, to the idea of hand-writing as the basis for legible text. When we write, we don’t measure each word and then expand or contract the space between those words so each line is the same length. When we run out of room, we simply start a new line, and though we have a ragged right edge, we have consistent spacing. The same is true of the earliest manuscripts of biblical literature, which were truly formatted to be read. I’m thinking of the Isaiah scroll, which I was privileged to see in Israel last year and is the primary model for my typesetting.

True, since the beginning of the printed book we have most often seen justified text, but back then they were much less discriminatory about word-breaks and hyphenation, so that consistent spacing was not an issue (i.e. imagine breaking the word “Her” after “He-”).

Unjustified text was revived by the likes of Gill and Tschichold early in the last century, and it continues to gain steam, especially in Europe. We are starting to see unjustified text much more frequently in every-day life, especially in digital form, and I would argue we are slowly becoming more accustomed to evenly spaced words than to uniform line-length. To me, justified type is really a Procrustean Bed. Too many times while reading have I leapt a great distance from one word to the next, only to be stunted by the lack of space between words on the very next line. I admit, I think justified text looks clean and orderly when done well, but it doesn’t do a single thing in the way of legibility. It is simply what we have been accustomed to for a long time, and since this project is partially about breaking down notions of how things “ought to be,” I ultimately decided to go with what I believe is the most legible approach; not to mention its suitability for ancient hand-written literature.

JMB: Bibliotheca will use the American Standard Version, and you’re planning to update the archaisms and make additional editorial changes based on Young’s Literal Translation. How extensive a revision of the ASV do you have in mind? What will the process look like?

ALG: While we’re on the topic I would like to touch on the choice of the ASV for this edition. Aside from being my favorite complete translation, to me, its literary character and formal accuracy make it the ideal choice for this project.

I appreciate and respect those who have other opinions, and I hope the success of this project will enable me to offer Bibliotheca in other translations. Obviously an unaltered Authorized Version would be wonderful, as would more popular contemporary translations. We will see.

As for editing the translation, aside from replacing the redundant archaisms (thee, hath, doth, etc.), modification will be extremely minimal. I will use Young’s Literal Translation (not my own whims) as an authority, and it will mainly function as a backup for syntax. If Young says something more plainly where the ASV is overly convoluted by Elizabethan, I will adopt Young’s syntax but will preserve the ASV’s vocabulary as much as possible. After all, Bibliotheca is for reading, and I believe using an even more literal translation for editing syntax is a safe limitation. In other words, I won’t be changing the ASV much at all; probably a fraction of one percent.

For those interested, I have added more details on the use of Young’s translation as an authority to the Editing the Translation section of the Kickstarter page.

JMB: I know the rapid success of Bibliotheca—you reached your funding goal in a little over 24 hours, and are set to surpass it by a considerable amount—was a pleasant surprise. It’s not over yet, and you may be too busy to indulge in speculation, but what do you think the outpouring of enthusiasm for Bibliotheca signifies to the world of Bible publishing?

ALG: I think the response to this project signifies that the biblical anthology is much too large (and I don’t mean in a physical sense) to be contained in any one format or type of reading experience. This is a diverse literature, which transcends time, culture and style in a way that very few have done, and none to the same extent. It has always taken on different forms within various contexts—artistic and technical, story-driven and study-driven. These forms will continue to change and, at times, surprise us.

I also believe that the increased ability to dynamically study the biblical literature through web-based technology creates space for a project like this—by which we experience the text exclusively as story—to exist and thrive.

JMB: Any thoughts on how Bibliotheca’s fundraising success will change and expand the scope of the project?

ALG: I thought I would be inching through this 30-day campaign toward the $37,000 goal. After reaching it in something like twenty-seven hours, and as I write this six days into the campaign, with twenty-three days left, that goal is nearly tripled and there are more than a thousand people behind the project.

So to answer your question, the scope of the project has already been changed by the overwhelmingly positive response of the backers. Their excitement, backing and sharing are making this into something that is at very least three times what I imagined, and that very well could be available in a second and third print run, in other translations and languages, and maybe even in book stores across the nation.

I know that’s big thinking, but Kickstarter has made it possible to deliver ideas directly to people who believe in them. They are the ones who decide which ideas will have a life beyond the campaign. Time will tell, but for now I am thrilled that Bibliotheca is becoming a reality, even if only this once.

In closing, I want to thank you, Mark, for backing the project and giving it such positive coverage. It is an absolute honor to have Bibliotheca featured, talked about, and scrutinized on your blog.

If this was an on-location interview, I would be admiring your legendary collection of rare bibles right now.

JMB: Thanks, Adam. I'm glad you could take the time from what I know has been a crazy week to share these thoughts with Bible Design Blog readers. If we were doing this on location, I'd give you free run of the library ... and while you were distracted, I'd help myself to those beautiful fonts!

The Bibliotheca Kickstarter campaign ends on July 27. If you haven't already backed Bibliotheca, I encourage you to do it. This will be a groundbreaking publication. Needless to say, you'll be reading more about it on Bible Design Blog.